- Thu 1 January 1970

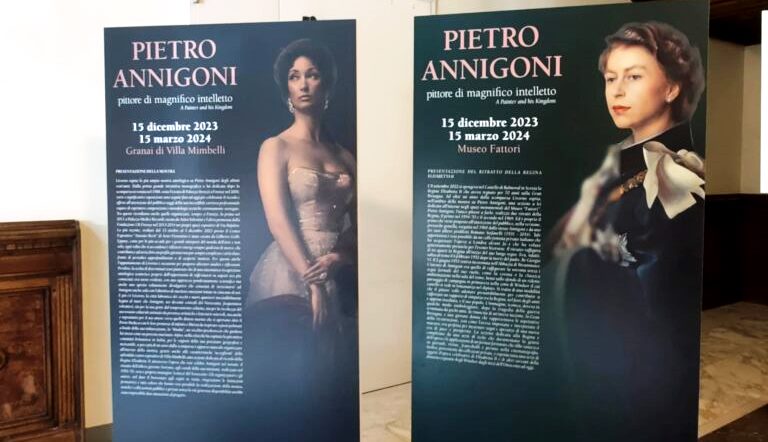

Exhibition “Pietro Annigoni, painter of magnificent intellect”

EXHIBITION OPENING

December 15, 2023 – March 15, 2024

Friday, Saturday, and Sunday: 10:00-13:00 | 16:00-19:00

Free Admission

INFO: Museo Civico G. Fattori – Tel. 0586/824606 – 824607 – infomuseofattori@comune.livorno.it

This is the most extensive anthological exhibition dedicated to Pietro Annigoni in the last twenty years, following the great monographic initiative realized at Palazzo Strozzi in Florence in 2000 to celebrate the artist after his death in 1988.

When the spotlight is on the great interpreters of the art world, something new always emerges. In-depth analysis and unexpected discoveries contribute to enriching profiles that are already known but still complex and articulated. This Livorno event is also an opportunity to propose further analysis and reflections.

In the central decades of the twentieth century, in fact, Annigoni often frequented the city of Livorno with its old and new neighborhoods inseparably linked to the sea. He appreciated its people with their straightforward temperament, but also the richness of its cultural fabric animated by countless artistic and literary presences of high intellectual caliber. Above all, however, he was attracted to and loved those expanses of sea that opened up beyond the Medicean Port with their promises of infiniteness and freedom, to be breathed in deeply aboard his own boat, the Bimba, an old fishing vessel that he himself piloted like an experienced sailor.

In addition to this privately lived passion for the sea, the exhibition in Livorno also reveals a public dimension that made the artist popular. Annigoni was the painter of portraits and self-portraits, testing grounds for his technical and expressive abilities in his youth and mirrors of his soul throughout his career. The portrait that made him known worldwide is particularly famous: the one he made of Queen Elizabeth II.

Thus, in the city that hosted the oldest British community in Italy, due to its geographical position and the important role played by its port in the Mediterranean, just over a year after the Queen’s passing, it seemed natural to organize a section dedicated to the portrait realized in 1954-55 by Annigoni of the then young Sovereign at the beginning of her mission, a portrait that has become a true iconic image of the twentieth century.

ANNIGONI

From a very young age, Pietro Annigoni practiced self-portraiture. Like many others before and after him, this genre represented, in the career of a figurative artist, one of the first testing grounds for one’s technical and expressive abilities, with a commitment that often continued, as in Annigoni’s case, until the extreme arc of one’s existential path. On display, we find the first essays he made as a very young artist, starting from 1927, when he was only 17 years old and already showing an extraordinary artistic maturity in his pencil drawings. Throughout his career, he experimented with all the techniques he had the opportunity to develop and consolidate over the years, from engraving to fresco, to fat tempera.

If self-portraiture, in addition to being a means of exercise accessible ‘at hand’, is also a kind of mirror of the soul, it is not escaped notice that the attitude, both in youth and in older age, is always characterized by a severe yet challenging self-image. Aware of his abilities and his craft, he confronts the contemporary world as a critical ‘actor’ but attentive to the complexity of everything that surrounds him and to the contradictions of his time.

FAMILY

Alongside the genre of self-portraits, the family environment revolving around the painter was another key point of reference for Annigoni. Beyond personal affections, close relatives were indeed ideal subjects for his visual and practical exercises, as they were more readily available. The Master’s parents, Ricciardo Annigoni and Teresa Botti, were the first to receive the artist’s attention, and in his early years, he created images of great formal perfection and emotional suggestion. The family, originally from Mirandola, had settled in Milan, where all their children were born: Nino, Pietro himself, and Ricciardino, the youngest. There remains a significant number of portraits of the father, Ricciardo, including one from 1928, one of Annigoni’s youthful drawings in pencil, of the highest artistic quality and among the most beautiful in his entire graphic production. In the exhibition, this drawing is accompanied by an equally extraordinary painted version from 1933, where the father is fully illuminated by an off-camera light source against a dark background in an atmosphere reminiscent of Flemish inspiration. The mother, Teresa Botti, of American origin and a homemaker, is also the subject of excellent drawing experiments. Among these, a stunning portrait created in pencil in 1928 should be highlighted.

Regarding his older brother Nino, there is no certainty that Pietro dedicated at least one portrait to him, while for the younger brother Ricciardino, there are various sketches and two completed paintings. The first captures him in his youth, and the second in a more mature moment while playing the guitar, an instrument he was passionate about. Unfortunately, a bitter fate befell the youngest member of the family, who passed away prematurely in 1945 upon his return to Italy after the war, due to the hardships and suffering endured during his captivity in Germany as an officer in the Italian army. After the closest family members, we come to his first love, Anna Maggini, whom he met in Florence in 1928 while he was attending the Academy of Fine Arts and she was studying harp at the Luigi Cherubini Conservatory. Anna was at the center of an emotionally intense but also contradictory relationship that ended in separation in 1957, after giving the Maestro two children, Benedetto in 1939 and Maria Ricciarda in 1948. There are various images of Anna in different techniques that document her unique beauty.

Young Annigoni was fatally inspired by her and continued to portray her even in more advanced and mature moments. From the aforementioned 1929 pencil portrait to the splendid gouache works of the early thirties, we move on to a series of oil paintings, some of which are unfinished, each capturing the face of a captivating woman. In these portraits, Annigoni seems to evoke a hidden inner torment and a suspended and distant sensuality through the expression of the eyes. The portraits of his children Benedetto and Ricciarda, from 1958 and 1970 respectively, represent models of male and, above all, female beauty that would be influential in the central decades of the twentieth century. Through the dissemination of prints and reproductions, they would find their way into the homes of ordinary people, along with the captivating splendor of Rossella Segreto, the Master’s second wife, whom he met in 1966 aboard the “Raffaello” transatlantic liner en route to New York and married in 1975.

ANNIGONI AND THE SEA

Pietro Annigoni had a very close relationship with the sea, influenced by his connections with Livorno and its people. In particular, he enjoyed fishing and, even more so, sailing. In this regard, he purchased an old fishing boat, “La Bimba,” with which, whenever he managed to carve out some free time from his numerous artistic commitments, he loved to move along the Tuscan coast up to Liguria. The exhibition, in this regard, offers interesting autobiographical insights, both directly and through the mediation of other artists. Thus, we find “La Bimba” sailing towards Portovenere during the summer of 1959, or small painted panels that document the Versilia coastline, around Tonfano, which the Maestro loved to visit, especially in the last years of his life. Annigoni, in its broader sense, loved the sea preferably in stormy weather because it evidently allowed him to express his atmospheric and chromatic visions to the fullest, often pushed to the limit of a harsh and hostile nature, as in “Partenza” from 1935, a canvas clearly inspired by the seventeenth century, where a group of sailboats faces a decidedly rough sea. In “Mareggiata” from 1971, on the other hand, the drama of a nighttime shipwreck is delineated, emphasized by a light source probably fueled by a rescuer’s torch, following a mode suggested by certain Flemish representations.

In his repertoire of turbulent waters, he couldn’t miss another historical reference to his favorite places during his Livorno excursions, the Tower of Calafuria, a visual testimony of ancient challenges between men and the elements of nature. Finally, “L’isola misteriosa,” relevant to Annigoni’s early artistic maturity, reflects specific iconographic references, in particular, Arnold Böcklin’s “Island of the Dead” from 1880-86.

THE MANNEQUINS

In the modern sense of the term, the author of this section, Anita Valentini, recalls how the genre emerged around 1914 from the relationship between de Chirico’s painting and the lyrical vision of Guillaume Apollinaire (1880-1918), a French writer and poet, creating an image of a faceless man that flowed into the artistic application of what would be called “metaphysical art.” Annigoni wondered why many painters, including himself, felt the need to paint mannequins. He wrote, “A mannequin can be nothing more nor less than a bizarre and picturesque object, worn out by use and abandonment, amusing, melancholic, and laden with memories, capable of stimulating our imagination. But it can be something else…”. After all, Annigoni himself owned several mannequins in his studio, each with various poses, transitioning from useful tools to bulky objects left in attics and cellars, becoming “eccentric and emblematic characters” that, as he wrote, “naked, torn, abandoned, with a human semblance, attract and captivate the artist’s gaze…”. In them, feelings of curiosity and amusement, as well as deep analysis of experiences lived and ongoing, are reflected.

Here, there is a risk of “splitting,” warns the Artist, which can be dangerously invasive, as the mannequin tends to become an autonomous character, possessing its own consciousness and judgment, before which, silent and ironic, we tend to remain alone with our unanswered questions, “…unaware that its fictional life is nothing more than our fragile reflection on the screen of the unknown…”. However, Annigoni’s conclusion is not entirely negative, although it leaves a bitter taste. In fact, he further writes, “I prefer not to forget that the mannequin always ends up making us smile, even when playing dramatic or tragic roles. Therefore, I consider painting mannequins a way to reconcile myself with men, making them fade from memory a little, especially when (all too often) they offer a spectacle of their obtuse and bestial madness.” Ultimately, the occasional ‘metaphysical’ reference of de Chirico becomes in Annigoni a more existentially oriented perspective regarding the present and the destiny of the human race.

THE STUDIO

Throughout his long artistic career, Annigoni had various studios where he practiced his profession. He also had one in London, in the Edwardes Square area, in the 1960s, but here we are primarily referring to his studios in Florence. He opened two studios in chronological succession in the 1930s and 1940s in Piazza Santa Croce, and then a third one in the subsequent decades, until his death, in Borgo Albizi near Piazza S. Pier Maggiore.

The fact that the Maestro documented his “workplace” multiple times, as the exhibition highlights in a dedicated section curated by Emanuele Barletti, is emblematic of the centrality that this space had in Annigoni’s life. He spent a significant part of his daily existence there, and it represented, as is customary for an artist, a sort of microcosm of his spiritual world. It was the designated place where, as he said, “…the only news that matters to me and drives me to work are my joys, my sorrows, my emotions, and my enthusiasms in the life that has been granted to me, in that world that is mine.” The studio was also, especially in his younger years, a “theatrical space” where all the elements he needed were present: models, mannequins, the light from the skylight, occasionally friends, students, and the tools of the trade. In this space of both physical and spiritual dimensions, Annigoni was the absolute master of himself, where he grappled with the experiences and challenges of his work, but also experienced an intimate creative joy that belonged only to him.

THE SACRED DIMENSION

There has been much debate about Annigoni’s actual relationship with the sacred dimension, especially considering that he created entire cycles of frescoes in some of the most important centers of the Catholic faith in Italy. Flavia Russo, in her essay in the catalog and through the selection of the exhibition, effectively summarizes this relationship through Annigoni’s own words: “I am, like many today, a man without the gift of Faith, but I am nostalgic for God… I believe that (even though I am the son of anticlerical anger) the nostalgia for a certain and revealed Faith in the Divine has deep roots in my spirit and defines an essential, albeit contradictory, trait that is reflected in my actions as a man and an artist.”

“The nostalgia for God,” Russo emphasizes, “is a feeling that permeates his entire life and leads him to seek occasions and places that can bring him closer to this missing gift. For Annigoni, art is not just a means of expression but also a means of knowledge. Therefore, painting sacred themes is the possibility of encountering the protagonists of the revelation he feels so distant from. Furthermore, the large cycles of frescoes in ecclesiastical settings, such as the Abbey of Montecassino or the Basilica of St. Anthony in Padua, allow the master’s work to reach a broader audience and break free from the domestic rooms to which portraiture often relegated him. The sacred-themed canvases consecrate the universality of Annigoni’s work, strengthen the connection with tradition, and open up a dimension of compositional imagination that he holds dear.” The exhibition thus provides an emotionally powerful opportunity to engage with religious themes in which we recognize the Master’s attention to the past and its iconographic models but also opens the door to a more intimate, introspective interpretation. Here, doubts and reflections intertwine with the contradictions of the present time, in search of possible redemption and an alternative light in the face of the abyss presented by the most perverse aspects of human nature.

THE FEMININE UNIVERSE

The figurative approach to the representation of the human body should encompass the entire and extensive graphic and pictorial production left to us by Pietro Annigoni. In the direction of the exhibition and catalog, we wanted to focus our attention on the relationship between Annigoni and the other ‘half of the sky,’ which, fundamentally, is for him a primary source of inspiration. It is an act of love and a ‘mission’ through a world of extraordinary compositional and psychological research. The selection of works presented to the public is sufficiently illustrative of a wide range of intentions, with a primary focus on studies specifically devoted to the nature of the female body, the ‘nudes,’ which the painter ‘describes’ from a young age with dynamic expressiveness and without false modesty, aimed at exalting both the physicality and beauty, even in its most sensual aspect, from initial sketches to more organically defined poses.

The ‘female nudity,’ just like the male nudity also explored by the artist, serves as a means of knowledge but also as a way to fit into constructed spaces where the external view of a composition, as in frescoes, implies full control over the physical form beneath the clothing, as it was done in the past.

Certainly, the extreme freedom of the nudes, not strictly aimed at another purpose but complete in themselves, created by the painter in his early years, may surprise. Some of the examples displayed here reveal the vital presence of young models posing with vivid realism, which Annigoni wishes to highlight in the purity of their early maturity. There are also later examples, executed more summarily in mixed media or watercolor, but where one can still appreciate the confident strokes that outline morphologies and postures with apparent ease and mastery.

On another level, but still with that emotional passion that characterizes the Maestro’s relationship with the female gender, are the portraits. Portrait painting, after all, is universally recognized as one of the components that made Annigoni famous worldwide, especially after the creation of the first portrait of Queen Elizabeth in 1954-55. In the exhibition, there are several well-defined portraits executed in mixed media and oil, showcasing psychological depth. Among these, the grand portrait of Baroness Stefania von Kories stands out. She was a noblewoman of German origin born in New York and naturalized as a British citizen, residing in the Chelsea neighborhood of London. She was known for her generosity and her civil commitment in the field of charity and assistance to the underprivileged, which she personally dispensed. The portrait, from 1958-59, is truly imposing, not to mention the largest (3 meters x 2), featuring a frontal image of a woman standing with rare almost Mediterranean beauty, adorned sparingly, and with unparalleled posture.

LANDSCAPES

Pietro Annigoni, like few others, was able to explore the theme of landscape in various visual and inner modulations that marked his long human and artistic journey. For him, the landscape was, first and foremost, observed from life. As a young man, between the 1930s and 1940s, he developed the habit of undertaking long journeys on foot through central and northern Italy and some European countries, particularly in the direction of Austria and Germany. During these journeys, he would observe and “archive” places and people he encountered along the way through sketches and drawings in notebooks and albums. By doing so, he developed an extraordinary visual memory that allowed him to recall locations and human presences assimilated from his experiences while also making extensive use of his imagination.

This approach enabled Annigoni to create a vast repertoire of images resulting from his personal “Grand Tour,” which continued into later years, albeit with the convenience of modern transportation that took him around the world in the mid-20th century. He drew important inspiration from the observed and experienced landscapes to create and construct large compositional designs such as frescoes. However, he also cultivated the taste and pleasure, often in the company of friends and students, of painting small outdoor views on easels in the vicinity of Florence. This allowed him to meet the many requests from people eager to own one of his works.

For Annigoni, nature is often seen in its ancestral and vitalistic component, where mysterious forces and energies come to life. His childhood haunts, excursions around Florence, and summer days spent in Versilia and on Lake Massaciuccoli are different but complementary moments in his personal life journey, where he encounters the many inspirations that enrich his formal repertoire.

The theme of “travel,” which encompasses many of Annigoni’s landscape scenarios, expands from the “courtyard of home” to Europe and the world. He left behind a large number of sketches and completed drawings from his travels. Beyond the world’s itineraries, landscape in Annigoni’s work serves as a mental and visionary elaboration that finds a “noir” dimension, dark and unsettling, in its relationship with nature, filled with mysterious “presences” and real or presumed ghosts.

This aspect of Annigoni’s art is not entirely understood or comprehensible, seemingly rooted in a fundamentally pessimistic perception of the reality around him. This includes the social miseries he observed and investigated in his youth, the aftermath of the Second World War, the sometimes chaotic and disordered reconstruction, international tensions between opposing blocs, and the risk of global nuclear conflict. These “criticalities” are likely compounded by the artist’s personal torments and the deeper currents of his feelings, which, however, are known only to him. In such a context, nature is no longer the image of the true reality but becomes a transfigured instrument for everything that passes through the mind and the “magnificent intellect” of the Maestro, representing his interpretation of the hidden paths of the human soul.

ANNIGONI AND DE CHIRICO

The exhibition has presented a brief comparison, more extensively explored in the catalog pages curated by Victoria Noel-Johnson, between Giorgio de Chirico and Pietro Annigoni. De Chirico was 22 years older than Annigoni, who always regarded him with respect and was somewhat influenced by him in his early maturity. De Chirico, in turn, had this to say about his younger colleague: “…he works seriously and goes straight down his own path without caring about the chatter, snobbery, or intellectualism of our times…” Such praise, coming from the “pictor optimus,” who was not known for being indulgent towards the contemporary art scene, almost sounded like an endorsement. The exhibited works include a comparison between the self-portraits of these two protagonists, both of whom exude a proud and defiant spirit, along with a sense of challenging the contemporary world, albeit with distinct and highly individual character traits. The comparison also extends to their unconventional spatial compositions of still lifes and views of walled gardens that evoke the classical image of the “hortus conclusus.”

ANNIGONI AND MATARESI

In the city of Livorno, which hosts the exhibition, it was only fitting to pay specific tribute to one of the leading figures of 20th-century Labronian painting: Ferruccio Mataresi (1928 – 2009). Mataresi, 18 years younger than Annigoni, was his student and friend, and he shared with him, even before a common figurative vision, a similar spirit of freedom and straightforwardness, which is inherent in the most genuine Livornese temperament. For the first time after his death, the curator of this section, Fabio Sottili, presents a significant selection of Mataresi’s works, including some true masterpieces like “Il macellaio” (The Butcher) or “Ritratto del Baritono Checchi” (Portrait of Baritone Checchi). “Il macellaio” is placed directly next to Annigoni’s “Cinciarda” in the exhibition, creating a powerful and highly suggestive juxtaposition. Mataresi was a prominent figure in Tuscan art, especially during the mid-20th century when Livorno was a hub for cultural and literary initiatives, artistic movements, and various awards in a lively climate of critical discourse. Like Annigoni, Mataresi applied his talent and professionalism to drawing and the practice of painting techniques, leaving us with examples of undeniable charm, such as still lifes in tempera and watercolor views of Livorno, as well as portraits in sanguine or ink, reflecting his artistic commitment nurtured by contact with Annigoni and within the context of the Labronian artistic tradition of the 20th century.

SANGUINE

Sanguine, created with red blood-colored pastel or chalk on paper, represents one of the most frequently used techniques by Pietro Annigoni. It was developed more or less concurrently with the creation of the large fresco cycles between the late 1930s and the 1980s, from the Convent of San Marco in Florence to the Basilica of the Saint in Padua. It is particularly suitable for the study of the human figure, thanks to its versatility in both sharp lines and soft shading, making it ideal for executing extensive and warm volumetric compositions on medium to large-sized sheets. The use of grid lines also allows for accurate measurements of proportions within the compositional space.

While primarily a technical tool, sanguine works also had a commercial purpose. Annigoni’s extensive production of these study and research pieces often focused on individual morphological components. They were, however, sufficiently complete and aesthetically suggestive to make them highly sought after by clients. Sanguine highlights the painter’s talent in drawing, which is the primary source and foundation of Annigoni’s artistic work. This section, curated by Luca Leoni, presents a small selection of examples, although similar works can be seen in other areas of the exhibition. These examples illustrate a diverse range of subjects, including a rare and beautifully executed self-portrait in sanguine from the early 1980s, displayed here. Typically, in the later stages of his life, Annigoni preferred to depict himself in tempera, so a self-portrait with such strong chiaroscuro is particularly noteworthy for the expressive quality achieved through the careful and calibrated application of shading.

From a technical exercise for study, analysis, and research aimed at defining organic and complex compositional images, sanguine evolved into an independent genre in a smaller format. This adaptation catered to the demand of the art market, which had a particular interest in Annigoni during the latter half of the 20th century. These works often drew inspiration from his frescoes, and they typically featured male or female portraits. Another successful stylistic and commercial avenue within Annigoni’s repertoire during the 1970s and 1980s was lithography.

Subscribe to the newsletter to stay updated

Don't miss any news about events in Livorno and surroundings.